There wasn't one single lightbulb moment that got me thinking that I might have postpartum depression (PPD) in the weeks after giving birth. There were little ones — lots of them.

Like how I cringed every time someone told me to "savor those newborn snuggles!" because all I wanted was for my baby not to be a newborn anymore. Or how I'd cry over bizarre things like not having the capacity to put the fresh flowers a well-meaning family member had brought over into a vase. Or how my brain would completely shut down any time my baby started to cry, and I'd spiral into thoughts about how, if I were a good mom, I'd know how to make him stop.

After a couple of weeks of this, my partner gently suggested that I talk with a therapist, who could help me figure out if I was dealing with PPD and how to cope. I wish I'd have brought it up myself sooner, but for a while, the idea that I was in the throes of a major mental health crisis from having a baby, that I wanted and loved, was honestly too embarrassing to admit, even to myself.

My experience isn't uncommon, though. In fact, 1 in 5 moms experience depression either during pregnancy or in the first year after childbirth, according to Postpartum Support International.

Speaking up about your negative emotions as a new mom can feel weirdly difficult. "You might be thinking, this should be the happiest I've ever been. This should be the most fulfilling thing I've ever done. But you just don't feel it. And that can cause shame, confusion and isolation," says Molly Vasa Bertolucci, L.C.S.W, P.M.H.-C., a perinatal mental health therapist based in California.

You might worry that your feelings mean you're not cut out to be a mom, or worse, that you don't really love your baby. (These things, of course, are not true. Having PPD doesn't mean that there's something "wrong" with you, and it's never your fault.)

Read This Next

But speaking up is important. Being honest about your emotions can help you feel less alone and is the first step towards getting the help you need to feel better. If you're unsure where to start, here's how to open up and get the help you need — and deserve.

Warning signs of postpartum depression include crying, persistent feelings of sadness, disrupted sleep, irritability and more.

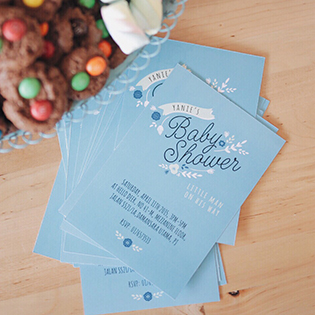

Speaking up to both your loved ones and a medical provider can help you feel better — ASAP.

You absolutely deserve to enjoy your new bundle of joy, and talking about PPD can be one of the first steps to help you do just that.

How do I know if I have PPD?

Postpartum depression is a serious medical condition and a type of depression that affects some moms. It can occur any time in the first year after giving birth, most often hitting within a two-week to a month postpartum. However, it can also develop as you get deeper into postpartum, especially around the 3 to 4-month mark when your baby may be experiencing a sleep regression.

Of course, every woman's experience of PPD is a little different. But in general, it's common to feel intensely sad or overwhelmed or paralyzed by the stresses of caring for a baby. You might have frequent mood swings and bouts of crying, and feel anxious or exhausted. You might also notice that you're not interested in the things you normally enjoy and feel indifferent or uninterested in your baby. (This screening quiz can help you determine whether you might be experiencing symptoms of PPD.)

Why you should tell someone you have PPD

Postpartum depression is a serious medical condition. It can show up as feelings of sadness or anxiety that just won't go away, sleep problems, having fears of being alone with your baby or intrusive thoughts or severe anxiety, among other symptoms. But it is treatable with talk therapy and/or medication. Without help, it can get worse — those feelings could linger for months or even years, research suggests.

That's why it's 100% worth saying something when you sense that things are off, so you can get the care and support you need. "You don't have to white-knuckle it," Bertolucci adds. Telling your partner or someone else you trust sets the ball in motion for you to start climbing out of that place. Plus, there's a good chance that your partner or loved one will be able to support you more effectively when they know how you're feeling. (And in some cases, it might turn out that your partner is dealing with similar struggles.)

Talking and getting treated isn't just good for you, by the way. It's also the best thing for your baby. PPD can make it harder to bond with your newborn and tend to their needs, not to mention, if not treated, it can last for years. "You think you're doing the right thing by suffering through it, but you won't be at your best,” says Sheila Chhutani, M.D., an ob/gyn at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas and a member of Texas Health Physicians Group. “It's really important for women to take care of themselves. Once we do, we're able to do better and give better."

How to tell a partner, family member or friend you think you have PPD

There's no right or wrong way to talk about how you're feeling. The most important thing is that you share what's been on your mind in a way that feels comfortable for you.

You don't have to make it formal or complicated, Bertolucci says. Just start with something simple like, "I'm not feeling like myself. So far, having a baby and being a mom have not been what I expected. I think I might have symptoms of postpartum depression and I need some extra support to get through this."

Chances are that as soon as your partner or support person hears that you're sinking, they're going to want to do what they can to lift you back up. They love you — and they want you to feel your best!

In the unfortunate event that they aren't supportive, you can — and should — move forward on getting help without them. When it comes to parenting and motherhood, "this may be the first of many opportunities to set boundaries that other people might not agree with,” Bertolucci says. “You get to make the decision for you."

How to tell a doctor or medical professional you may have PPD

It's typical for an OB/GYN to ask about PPD symptoms or give you a PPD screening test at your postpartum checkup. Your baby's pediatrician may do the same at your baby's checkups. If that happens, feel free to lay it all out — you don't have to hold back.

If your doctor or your baby's pediatrician hasn't directly asked about PPD, don't hesitate to say something like, "Can we talk about postpartum depression? I think I may have some symptoms."

In most cases, your doctor will want to get a better understanding of what you're feeling. From there, they may refer you to a therapist, who you can talk to in more detail about what's going on, says Dr. Chhutani. If you feel like your provider is brushing off your concerns, you should find another doctor ASAP, says Dr. Chhutani.

That said, you definitely don't have to wait for your initial postpartum appointment or one of your baby's checkups to bring up any concerns related to your mental health. "If a patient is struggling before the six-week visit, they should call so they can come in sooner," Dr. Chhutani says. (However, if you're experiencing serious symptoms like being unable to take care of yourself or your newborn, feeling like others are better off without you, or having thoughts of harming yourself or your baby, don't wait to see the doctor. Call 911 right away.)

How to navigate care for PPD

If you need help finding a therapist specializing in PPD, Postpartum Support International has an online directory of therapists, and their website is a great place to start. "You can also go through your insurance and ask for in-network providers who treat perinatal mental health," Bertolucci says. Just make sure to confirm whether or not you need a doctor's referral for the sessions to be covered before booking an appointment.

Once you have a therapist and it's time to talk, try to share as much as you can — when the feelings started, how severe they are and how they're impacting your day-to-day life.

"Many women may not open up about what they are experiencing due to feeling ashamed or guilty, or fear of being judged (even by their medical provider)," says Nicole Taylor., M.D., perinatal psychiatrist and member of the What to Expect Medical Review Board. "Some women believe that if they talk about how they are feeling, they may be seen as bad mothers or even have their children taken away. And some women may also believe this makes them weak or not woman enough — but these are myths, she adds.

"If you had a friend or sister who was struggling, wouldn't you want to know? Wouldn't you want them to tell you so that you could help them or find someone who could help them," says Dr. Taylor.

You might say, for instance, that you started feeling very sad for no reason and weren't bonding with your baby about two weeks after giving birth, and that sometimes you start crying when you can't soothe the baby and have no interest in getting outside for walks even though you normally really enjoy that.

Together, you and your therapist can pinpoint what you're struggling with and figure out ways to deal.

It’s possible that medication will be part of your treatment plan, Dr. Chhutani says. There are traditional antidepressants and anti-anxiety meds, which are safe to take while breastfeeding. Another option is Zurzuvae (zuranolone), the first oral medication specifically for PPD, which was approved by the FDA in 2023.

As you're seeking help for PPD, remember: The more you voice your needs, the better they can be met. There's no right or wrong way to go about receiving care, but these tips can help.

Ask for the help you actually need. It might be a few hours of child care so you can meet with a therapist or a support group, someone to tackle the ever-growing mountain of laundry or the chance to take a nap on a Saturday afternoon.

Tell as many (or as few) people as you want. You don't have to broadcast the fact that you have PPD to everyone, but you also don't have to keep it a secret. Who you share your feelings with is entirely up to you. But the more trusted people you open up to, the more support you may receive in return.

Bring someone to your doctor's appointment. Having someone with you can help you make sure you're taking in all the information the doctor is telling you, especially if it seems overwhelming.

Try a support group. These can be found at local hospitals, family planning clinics or community centers. You can also tap into the National Women’s Health Information Center, Postpartum Support International, the National Library of Medicine and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for more information on and resources.

You might feel like a weight is lifted off your shoulders the moment you open up about your symptoms. But real change, and that sense of truly feeling like yourself again, may come more slowly over four to eight weeks, whether you're talking to a therapist, taking medication or both.

Remember, having PPD isn't your fault and it doesn't make you a bad mother. You're experiencing a mental health problem that's very common — and very treatable. No new mom is an island, and that's even more true for those who are struggling with PPD. Opening up about your symptoms can be hard, but it's the best thing you can do to start feeling better.